Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Semirecursive Relations

- Recursive Sets

- Recursive Enumerable Sets

- Reductions and r.e. completeness

- Post’s Problem

From the set of natural numbers, \(\mathbb{N}\), we can generate a lot of subsets \(S \subset \mathbb{N}\). In fact, the number of subsets we can have of \(\mathbb{N}\) is so large that it’s uncountable. This study of subsets on \(\mathbb{N}\) is a complicated branch of mathematics and logic, and it serves to describe and answer questions in computer science on computability.

Note: We will be alternating some commonly used notations.

- \[\phi_e(x) \equiv \{e\}(x)\]

Why You Care: $|P(\mathbb{N})| = \aleph_1$

We prove this by stating a more powerful claim: there does not exist a bijection between a set and its powerset. For set \(S = \emptyset\) , it is trivial: \(|S| = 0 \neq |P(S)| = |\{\{\}\}| = 1\) . So suppose it’s non-empty, and it does have a bijection by contradiction, \(f : S \to P(S)\). Then, we look at the following set, \(B = \{s \in S : s \not\in f(s)\} \subset S\) This is obviously a well constructed set \(B\). It contains all elements $s$ such that the bijective mapping $f(s) = S \not\ni s$ , i.e. does not contain $s$ itself. There must exist a \(b \in S\) such that \(f(b) = B\) since to be bijective, \(f\) must also be surjective(i.e. \(\forall X \in P(S), \exists x \in S, f(x) = X\)). Then, let’s analyze two cases:

- \(b \in B\). Then by definition, \(b \in f(b) \implies b \not\in B\). Contradiction.

- \(b \not\in B\). Then by definition, \(b \not\in f(b) \implies b \in B\). Contradiction.

Both cases give us contradiction, then the bijection is absurd for any arbitrary set \(S\). Furthermore, we can take the powerset of any uncountable set and reach a higher uncountable ordinal.

This is important because although \(\mathbb{N}\) may be countable, analyzing the subsets of \(\mathbb{N}\) can prove to be much more complicated, and yields surprising results. The fact that we have countable recursive functions that we can program in C, but uncountable number of functions with arbitrary domain and range means there are some unexplored complexity in computability. We aim to analyze this uncountable set, which turns out to have some interesting results, and we will eventually arrive at theorems of Tarski, Godel, and Church.

Semirecursive Relations

Before we dive in, we should revisit the Halting Problem as explored by the previous blog. For a given program, we want to know whether it terminates. Intuitively, we would be able to say “yes” eventually if the program does indeed terminate, but we would never be able to say “no”, since it requires infinite time for us to wait before we answer.

This is a semirecursive relation, asking “Would the program with code \(\hat{f}\) halt on input \(x\)” a given program. To put it more formally, \(R(x) \iff f(x)\downarrow, \quad f\text{ is recursive}\)

Additionally, it is equivalent to saying, “would there exist an output from the program?”, which is: \(R(x) \iff \exists y P(x,y)\) Basically, semirecursive relations are ones that have a positive answer and may not have a decidable answer otherwise. We also denote these relations to be \(\Sigma_1^0\) relations.

Some important closure properties of semirecursive relations:

- Disjunction: \((\exists y) Q(x, y) \lor (\exists y)R(x,y) \iff (\exists u)[Q(x, u) \lor R(x,u)]\)

- Conjunction: \((\exists y)Q(x,y) \wedge (\exists y)R(x,y) \iff (\exists u)[Q(x,(u)_0) \wedge Q(x,(u)_1)]\)

- Existential Quantifiers: \((\exists z)(\exists y)Q(x,y,z) \iff (\exists u)[Q(x, (u)_0, (u)_1)]\)

- Bounded Universal Quantifiers: \((\forall i \leq z)(\exists y)Q(x,y,i) \iff (\exists u)[Q(x, (u)_i, i) \forall i \leq z]\)

- Recursive Characteristic Functions: \(Q(x) \iff P(f_1(x),...,f_m(x))\)

However, note that it is not closed under unbounded universal quantifiers. Intuitively, if you had to make sure for every number, some relation is true, you’d have to run your program infinitely many times, without termination. Meanwhile, for a semirecursive relation, it must give us a positive answer in finite time. Consequently, it must also not be closed under negation, i.e.

\[H(e,x) \iff (\exists y)T(e,x,y)\]is the halting relation, and \(\lnot H(e,x) \iff (\forall y)[\lnot T(e,x,y)]\).

Recursive Sets

One way to analyze the high complexity of subsets on \(\mathbb{N}\) is to see what kind of sets we can identify from algorithms. Recall the Church-Turing thesis states that algorithms and recursive partial functions are equivalent. By definition, a set \(A\) is recursive if we can say “yes, \(x \in A\)” via a recursive function and “no, \(x \not\in A\)” similarly. Then, we can just ask from 0 onwards whether an element is in the set. For example,

Q: “Is 0 in A?”, A: runs some algorithm… Yes

Q: “Is 1 in A?”, A: runs some algorithm… No

Q: “Is 2 in A?”, A: runs some algorithm… Yes

…

Then \(A = \{0,2,...\}\) for this specific example.

Recursive Enumerable Sets

then the definition is defined rigorously as the following:

A set \(A \subset \mathbb{N}\) is recursively enumerable (r.e.) if \(A = \emptyset\) or \(A = \{f(0),f(1),f(2),f(3),...\}\), where \(f : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\) is a total recursive function. Similarly, a set \(A\) is co-recursively enumerable (co-r.e.) if \(A^c\) is r.e.$$.

We will prove some properties about them below:

- \(A\) is r.e. \(\implies A = \{x \mid g(x)\downarrow\}\) . What this means is that \(A\) is the domain of some partial recursive function \(g\). We know \(A\) is the enumeration of \(f\), then \(\forall x, \exists y, T(\hat{f}, x, y)\) by Kleene’s Normal Form theorem. Then, we define the partial \(g(y) := \mu_z [ T(\hat{f}, (z)_0, (z)_1) \& U((z)_1) = y]\). By definition, \(g\) will only converge on some \(y\) if it is the result of some computation where the input is \((z)_0\), and the output computation state is \((z)_1\). We solved for both unknowns using Godel coding to dovetail.

- We can further allow \(f\) to be injective if \(A\) is infinite. We define \(B = \{ z \in \mathbb{N} \mid T(\hat{f}, (z)_0, (z)_1) \& \forall n < z,[T(\hat{f}, (n)_0, (n)_1) \implies (z)_1 \neq (n)_1]]\}\). This set \(B\) is a set that contains all inputs and outputs of \(f\) such that the output cannot be the same for two different inputs, i.e. the definition of injection. \(B\) is recursively enumerated by some recursive total function \(g\), since it is clear that we can write a function that asks for \(\mu_z\) of that giant predicate describing the set, then simply define \(\bar{f}(n) = (g(n))_1\) then \(\bar{f}\) enumerates the outputs of the original function \(f\) injectively.

- The relation \(x \in A\) is semirecursive. This is true since \(x \in A \iff \exists n [ f(n) = x ]\). Since \(f\) is recursive, this is by definition a semirecursive relation. This has some implications. Given \(A,B\) recursive enumerable,

- \(A \bigcup B\) is also r.e.

- \(A \bigcap B\) is also r.e.

- \(A^c\) is not always r.e. - it is co-recursively enumerable. If \(A\) and \(A^c\) are both recursively enumerable, then \(A\) is recursive.

- \(f[A]\), and \(f^{-1}[A]\), i.e. the image and inverse image of \(A\) under \(f\) is r.e.

For sake of brevity, I’ll list out a few properties without proofs (which can be found online):

- A set is recursive iff it can be enumerated by a total, monotonically increasing \(f : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\) .

- The halting set defined as \(H' = \{x \mid H((x)_0, (x)_1\}\) is recursive enumerable, but not recursive. Recall \(H(e,x)\) is true if the partial function coded by \(e\),taking in the input \(x\), converges, i.e. \(\phi_e(x) \downarrow\). (Think about what it would imply if \(H\) was recursive)

- Post’s Diagonal is defined as \(K = \{x \mid \phi_x(x) \downarrow\}\). This is slightly more elegant than the halting set, but it is also recursive enumerable but not recursive.

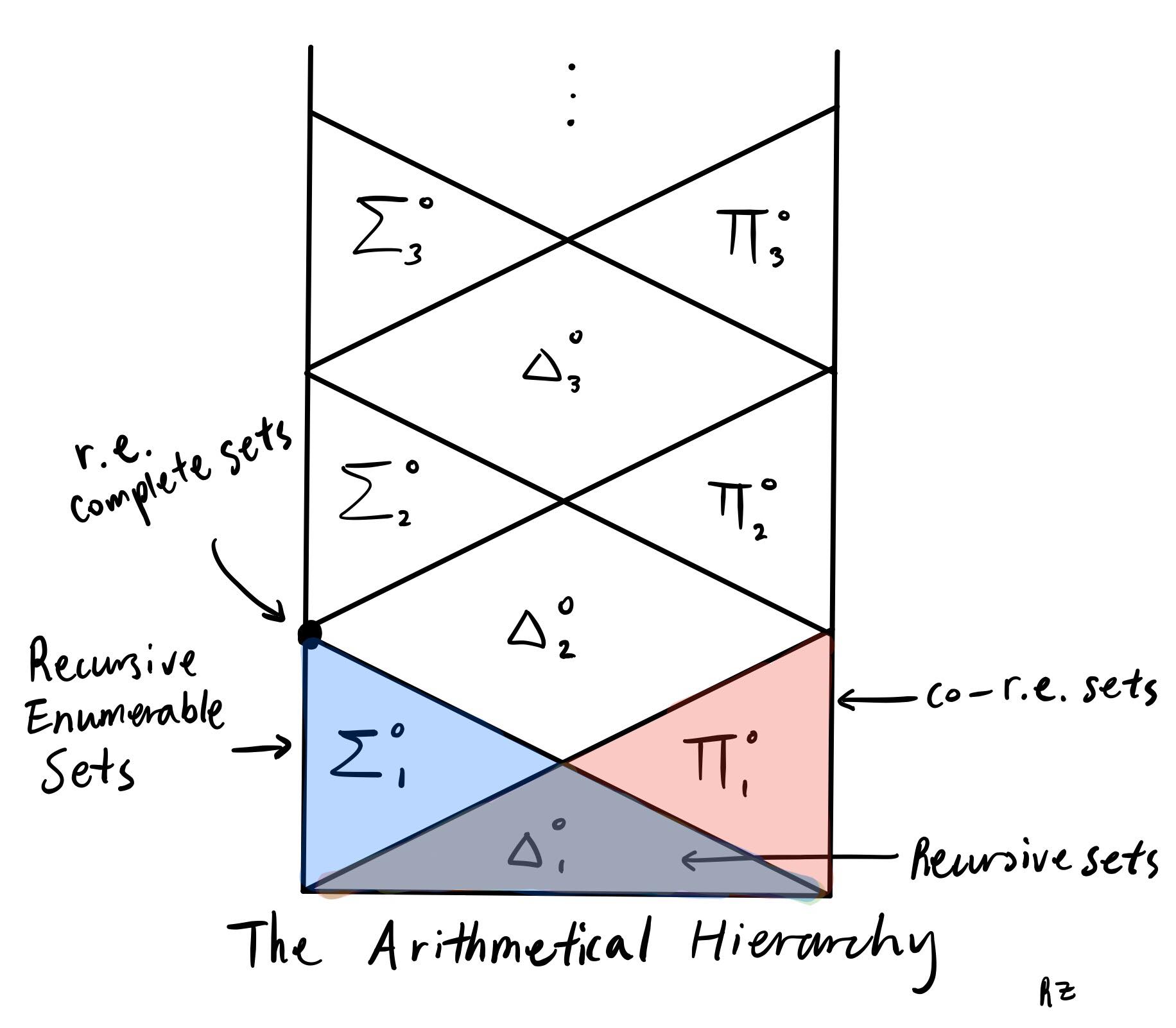

From what we learned so far, we can classify the sets into three sets:

- Recursive enumerable sets, we denote these \(\Sigma^0_1\).

- Co-recursively enumerable sets, we denote these \(\prod^0_1\).

- Recursive sets, we denote these \(\Delta^0_1\).

Then we have constructed the first level of a hierarchy of sets, where the intersection of recursive enumerable sets and co-recursively enumerable is the recursive set. Here’s an illustration of what I mean:

We will explore what the sets are in \(\Sigma^0_2\) and etc. later.

Reductions and r.e. completeness

In algorithms courses offered in CS, where one briefly visits the NP class of problems, the topic of NP complete problems show up. An NP complete problem is one which every other problem in NP can be reduced to. What is reduction? It means that we can use another problem in order to solve this problem. A quick example is, we can reduce the problem of Clique to a problem of Independent Set by inverting the edge set of the input graph, and if independent set returns some $K$, then we have a $K$ clique in our graph. Recall we cannot increase our input size exponentially or call the reduction exponential number of times, for it to be a reduction in that sense.

What does reductions and r.e. complete mean then? Well, basically the same, but applied to r.e. sets. Formally, a reduction from a set \(A\) to \(B\) is such that we can ask questions about membership in \(B\) to determine membership in \(A\). There is a hierarchy of “ease” of reduction by the following classifications:

- The reduction is \(A \leq_T B \iff \mathcal{X}_A \in \mathcal{R}(\textbf{N}_0, \mathcal{X}_B)\). In other words, the characteristic function of \(x \in A\) can be composed as a recursive (total) function which includes \(\mathcal{X}_B, S, Pd\) on \(\mathbb{N}\). We call this Turing reducibility.

- The reduction is \(A \leq_m B \iff [x \in A \iff f(x) \in B]\) if \(f\) is arbitrary.

- The reduction is \(A \leq_1 B\) if \(f\) in 2) is injective.

- The reduction is \(A \equiv B\) if \(f\) in 2) is bijective.

An r.e. complete set, denote A, has the property that every r.e set is 1-reducible to it, formally:

\[B \text{ is r.e.} \implies B \leq_1 A\]Intuitively, we must then assume that \(A\) must be a set that is bigger than or equal to any r.e. set, otherwise the injection won’t work. Then obviously \(A\) is infinite. For example, post’s diagonal \(K = \{e \mid \phi_e(e)\downarrow\}\) is r.e. complete. Here’s a proof.

For arbitrary r.e. set \(B\), it is defined as the domain of some recursive function \(f\), then \(x \in B \iff f(x) \downarrow\). Then, we define \(g(x,y) = f(x)\), so that it is independent of \(y\). Then there exists some code for \(g\), call it \(\hat{g}\), so that \(g(x) = \{\hat{g}\}(x)\). By the \(S^m_n\) theorem, \(S^1_1(\hat{g}, x)\}(y) = f(x) \forall y\). Then since any \(y\) applies, we ask \(\{S^1_1(\hat{g}, x)\}(S^1_1(\hat{g}, x))\) in \(K\). In other words:

\[x \in B \iff f(x)\downarrow \iff g(x,y)\downarrow \iff \{S^1_1(\hat{g},x)\}(S^1_1(\hat{g},x))\downarrow \iff h(x) = S^1_1(\hat{g}, x) \in K\]The \(S^m_n\) theorem states that \(S^1_1\) is injective, then it is obvious that \(h\) is injective, then \(B \leq_1 K\). Since \(B\) is arbitrary, \(K\) must be r.e. complete.

Post’s Problem

Emil Post, one of the founders of computability theory, asked a question that could not be solved until more than 20 years later. The question asks the following: does there exist r.e. sets $A$ and $B$ that are not turing reducible to each other?

The answer is yes. However, before we show this, we must dig further to find properties of recursive enumerable sets.