Probability Tidbits 7 - All About Integration

As we discussed in tidbit 5, random variables are actually functions. These functions are non-negative everywhere and importantly measurable. This means for any measurable set in the output measurable space (typically $(\mathbb{R}, \mathcal{B})$), the preimage of the measurable set must also be measurable in the input measurable space(arbitrary $(\Omega, \mathcal{F})$). Since random variables preserve measurability of sets, it’s natural to integrate over some measurable real number domain (e.g. intervals) to assign a probability measure to it.

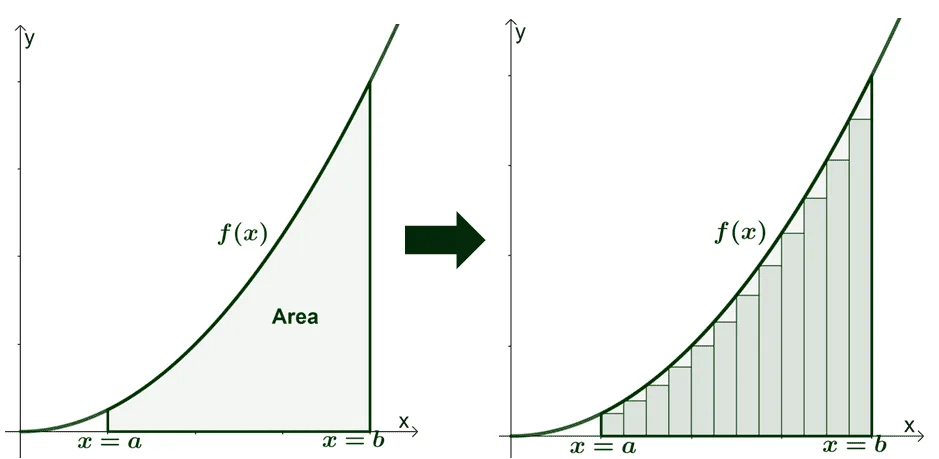

Recall in Riemann integration, we would approximate the integral of a function $f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ by taking tall rectangles of fixed length but variable height and fitting it snugly under the function. Then, we’d take the limit as the fixed lengths go uniformly to 0 in order to get the precise area under the curve:

When it comes to measurable functions mapping from arbitrary $(\Omega, \mathcal{F})$ to the reals(instead of reals to reals), it makes sense to construct these rectangles a different way, the Lebesgue way.

Note that for the rest of this blog we’ll be using measurable functions to mean positive measurable functions. Too many words to type.

Simple Functions

When considering measurable functions that map $\Omega \to \mathbb{R}^+$, what is the simplest function you can think of that’s not just $f(\omega) = 0 \forall \omega \in \Omega$? Suppose we fix an arbitrary measurable set $A \in \mathcal{F}$, then the indicator function of $A$ is pretty simple:

\[1_A(\omega) = \begin{cases} 1 \text{ if } \omega \in A \\ 0 \text{ else} \end{cases}\]This map basically partitions the space of $\Omega$ into elements that are in $A$ and those that aren’t. This function is obviously measurable, since $A$ is measurable and $A^c$ must be measurable since $\mathcal{F}$ is a $\sigma$-algebra. We can denote \(\mu(1_A) := \sum_\Omega 1_A(\omega) = \mu(A)\), in that we summed up all elements measures in $A$ with unit weights.

A function $f$ is called simple if it can be constructed by a positive weighted sum of stepwise indicator functions of measurable sets $A_1,…,A_n$ (finite!) in $\mathcal{F}$:

\[f(x) = \sum_k^n a_k 1_{A_k}(x)\]Subsequently,

\[\mu(f) = \sum_k^n a_k\mu(A_k)\]There are some obvious properties of simple functions. Let’s take $f, g$ as simple functions and $c \in \mathbb{R}$:

- Almost everywhere equality: $\mu(f \neq g) = 0 \implies \mu(f) = \mu(g)$.

- Linearity: $f+g$ is simple and $cf$ is simple.

- Monotonicity: $f \leq g \implies \mu(f) \leq \mu(g)$

- Min/max: $\text{min}(f, g)$ and $\text{max}(f,g)$ are simple.

- Composition: $f$ composed with an indicator function $1_A$ is simple.

Integrals of simple functions are also easy to reason about. Let’s start with a sequence of monotonically increasing simple functions $h_n$ such that the sequence converges to \(1_A\) for a measurable set \(A \in \mathcal{F}\). Is \(\text{lim}_{n \to \infty} \mu(h_n) \to \mu(1_A)\)? Or in other words, can we “pull out the limit”, so that:

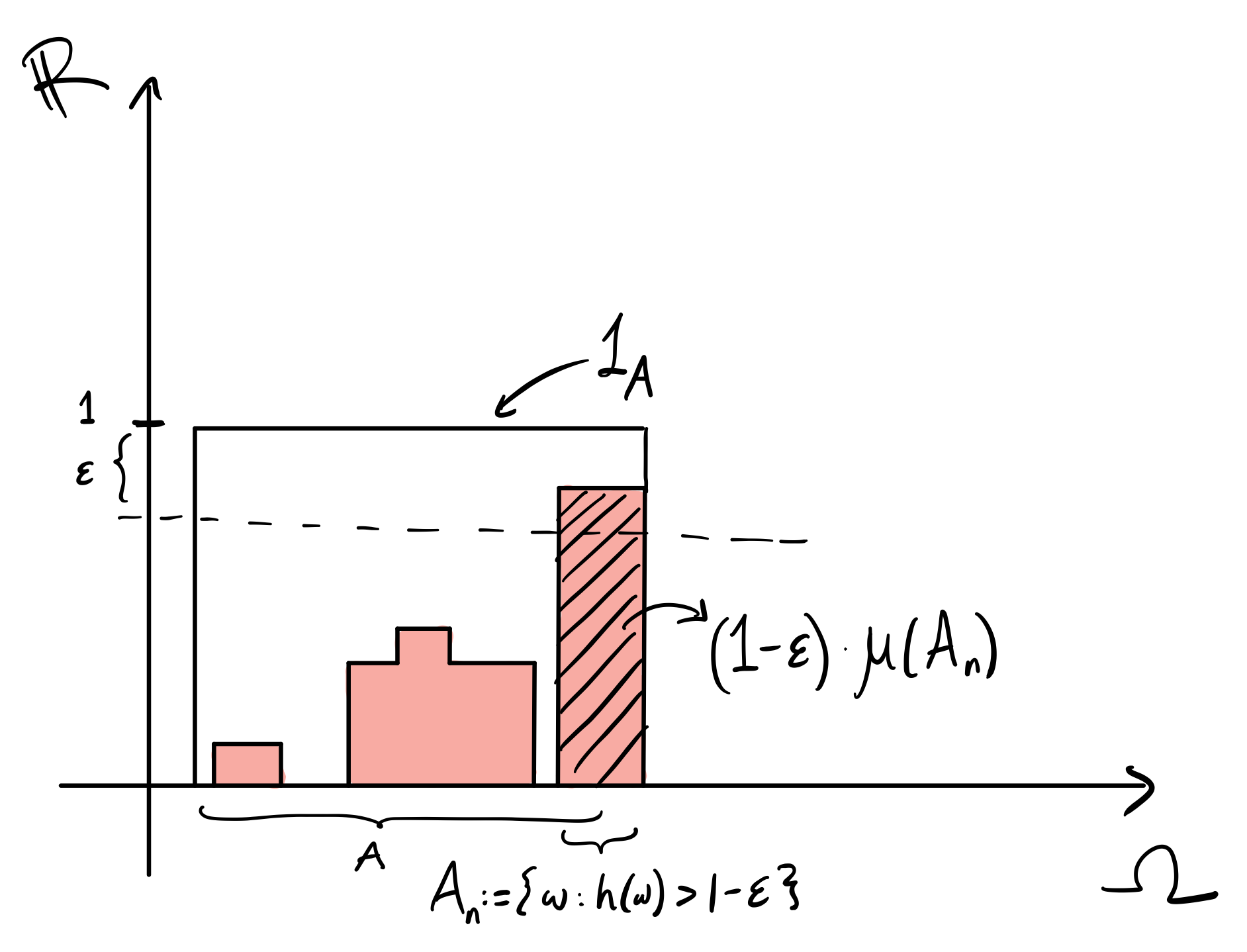

\[\mu(\lim_{n \to \infty} h_n) \stackrel{?}{=} \lim_{n \to \infty} \mu(h_n)\]We can correspond these functions $h_n$ to measurable sets \(A_n := \{\omega : h_n(\omega) > 1 - \epsilon\}\) for some $\epsilon$ (recall it’s also bounded above by the indicator functions). Note that \((1-\epsilon) \mu(A_n) \leq \mu(h_n)\) by definition, since it’s only a subset of the outcomes for $h_n$:

The sequence of sets $A_n$ converge to $A$ since \(h_n \to 1_A\) and \(A = \{\omega: 1_A(\omega) = 1 > 1-\epsilon\}\). This means \(\lim_{n \to \infty} \mu(h_n) \geq (1-\epsilon)\mu(A)\). Now we take $\epsilon$ small and we have that \(\lim_{n \to \infty} \mu(h_n) = \mu(A) = \mu(\lim_{n \to \infty} h_n) = \mu(1_A)\). Note that we started with a simple indicator function in the above example, but it can be pretty trivially extended to any simple function.

Measurable functions aren’t always simple. For an arbitary measurable $f : \Omega \to \mathbb{R}^+$ we can’t just represent it with a finite sum of indicator functions. Just like how we take the limit as the rectangles widths go to zero in the Riemann integral, we can take a limit on a sequence of monotonically increasing simple functions bounded by $f$. The integral of $f$ can thus be expressed as the integral of the least upper bound of these simple functions:

\[\mu(f) := \text{sup}\{\mu(h):h \text{ is a simple function}, h \leq f\}\]Monotone Convergence Theorem

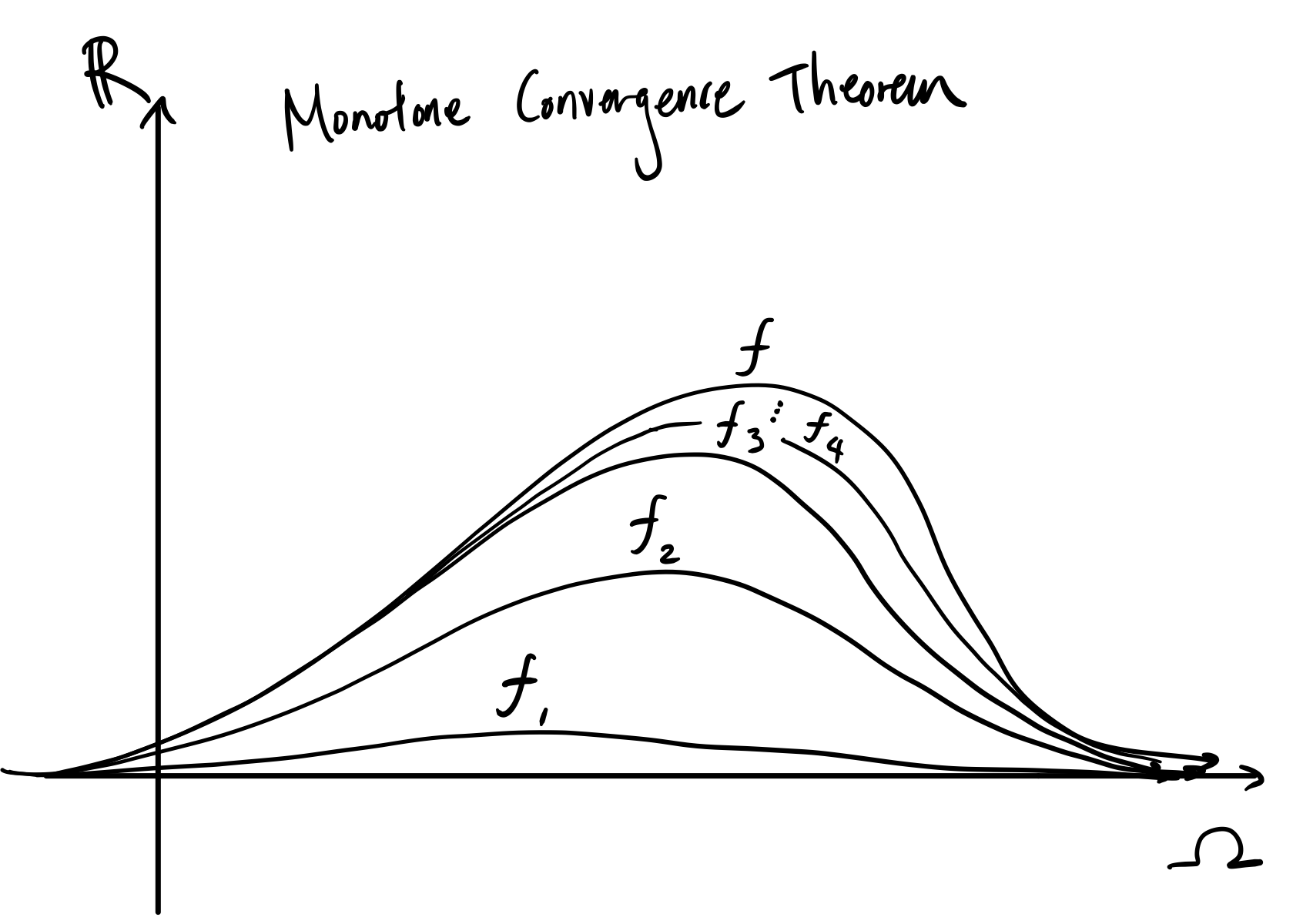

This theorem is basically the entire foundation of lebesgue integration. Just like how we built up integral approximations of continuous functions using rectangles, monotone convergence theorem tells us we can define the lebesgue integral using approximations of measurable functions using simple functions. Specifically, it states for a sequence $(f_n)$ of monotonically increasing measurable functions which converge pointwise to some function $f$, $f$ is measurable and the lebesgue integral also converges:

\[\lim_{n \to \infty} \mu(f_n) = \mu(\lim_{n \to \infty} f_n) := \mu(f)\]First, let’s fix $\epsilon > 0$ and some simple function $0 \leq h \leq f$. The set

\[A_n := \{\omega: f_n(\omega) \geq (1-\epsilon) h(\omega)\}\]is interesting (note that this is slightly different than the simple function case, since we’re using $\geq$ here). As $n \to \infty$, $A_n \to \Omega$ since $f_n$ will eventually converge to $f \geq h$. We know that \(\mu(f_n) \geq \mu(f_n 1_{A_n})\), since we’re restricting our domain to a smaller set $A_n$. We also know that \(\mu(f_n 1_{A_n}) \geq \mu((1-\epsilon)h 1_{A_n})\). Now we have a chain of inequalities which we can take the limit of:

\[\begin{align} \mu(f_n) \geq \mu(f_n 1_{A_n}) \geq \mu((1-\epsilon)h1_{A_n}) \\ \implies \lim_{n \to \infty} \mu(f_n) \geq \lim_{n \to \infty} \mu(f_n 1_{A_n}) \geq \lim_{n \to \infty} \mu((1-\epsilon)h1_{A_n}) \end{align}\]Note that since $h1_{A_n}$ and $h1_A$ are simple, from previous results on simple functions we have:

\[\lim_{n \to \infty} \mu((1-\epsilon) h 1_{A_n}) = \mu(\lim_{n \to \infty} (1-\epsilon) h 1_{A_n}) = (1-\epsilon)\mu(h)\]Since $A_n \to \Omega$. Since we took an arbitrary $\epsilon$, we can say that:

\[\lim_{n \to \infty} \mu(f_n) \geq \mu(h)\]And since we took an arbitrary simple $h$, we can say that:

\[\lim_{n \to \infty} \mu(f_n) \geq \sup_{h \leq f} \mu(h) := \mu(f) = \mu(\lim_{n \to \infty} f_n)\]by definition of the lebesgue integral on measurable $f$, so we’re done! Here’s an picture on what the $f_n$’s may look like:

You might be saying right now:

So what? Big deal you moved the limit from inside to outside. Why do we care?

Let me convince you this is a big deal, by using this theorem to trivially prove some other lemmas and theorems in integration theory which we’ll be using as hammers to problems in the future.

Fatou’s Lemma

We can easily prove Fatou’s Lemma (and its reverse counterpart) with monotone convergence theorem. The lemmas are useful to reason about bounds of a sequence of measurable functions which may not necessarily be monotonically increasing or decreasing. Specifically, the lemmas state that for a sequence of measurable functions $(f_n)$:

\[\begin{align} \mu(\liminf_n f_n) \leq \liminf_n \mu(f_n) \quad \text{(Fatou's Lemma)} \\ \mu(\limsup_n f_n) \geq \liminf_n \mu(f_n) \quad \text{(Reverse Fatou's Lemma)} \\ \mu(\liminf_n f_n) \leq \liminf_n \mu(f_n) \leq \liminf_n \mu(f_n) \leq \mu(\limsup_n f_n) \quad \text{(Fatou-Lebesgue Theorem)} \end{align}\]Here, we just have to look at \(g_k := \inf_{n \geq k} f_n\) which is an increasing sequence of functions on $k$, converging to some function $g_k \uparrow g$. We know that:

\[\begin{align} g_n \leq f_n \forall n \\ \implies \mu(g_n) \leq \mu(f_n) \forall n\\ \implies \mu(g_n) \leq \inf_{k \geq n} \mu(f_k) \\ \implies \lim_n \mu(g_n) \stackrel{*}{=} \mu(\lim_n g_n) = \mu(\liminf_n f_n) \leq \lim_n \inf_{k \geq n} \mu (f_k) = \liminf_n \mu(f_n) \end{align}\]In the result, the equality with a star on top is where we applied monotone convergence theorem and the rest were just by definition. You can essentially use the same approach to prove reverse Fatou’s lemma. The theorem follows pretty obviously.

Dominated Convergence Theorem

Dominated convergence theorem essentially says that if a sequence of measurable functions $f_n$ which converge to $f$ is bounded by a nice function $g$, then $f$ must also be nice. Here, we define niceness as $\mu$-integrable. For some measure space $(\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \mu)$ if a function $f$ is $\mu$-measurable it is denoted $f \in \mathcal{L}^1(\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \mu)$ if:

\[|\mu(f)| \leq \mu(|f|) < \infty\]where the first inequality is just due to Holder’s inequality.

So back to the theorem. It states that $(f_n)$ is dominated by $g \in \mathcal{L}^1(\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \mu)$ if:

\[|f_n(x)| \leq g(x) \forall f_n, x\]If this holds, then \(f \in \mathcal{L}^1(\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \mu)\), and \(\mu(f_n) \uparrow \mu(f)\) (we can pull out the limit) . We know by triangle inequality:

\[|f_n - f| < 2g \implies h_n := 2g - |f_n - f|\]Here, $(h_n)$ is a sequence of positive measurable functions. We can prove that $\mu(\mid f_n - f\mid)$ vanishes:

\[\begin{align} \mu(2g) = \mu(\liminf_n h_n) \stackrel{*}{\leq} \liminf_n \mu(h_n) = \mu(2g) - \limsup_n\mu(|f_n - f|) \\ \implies 0 \leq \liminf_n \mu(|f_n - f|) \stackrel{*}{\leq} \limsup_n\mu(|f_n - f|) \leq 0\\ \implies \lim_n \mu(|f_n - f|) \to 0 \end{align}\]where the starred inequality is due to Fatou’s lemmas.

Counterexamples to Dominated Convergence Theorem

Say we don’t have a dominating function $g$ for a sequence of functions $(f_n)$. Then it’s hard to say whether we can pull out the limit. Suppose we have the function \(f_n(x) = \frac{1}{x} * 1_{[\frac{1}{n}, 1)}\). \(\mu(f_n) < \infty \forall n\), but the limit is the integral of \(\log(1) - \log(0) = \infty\). Here we couldn’t bound $f_n$ by any dominating function in \(\mathcal{L}^1(\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \mu)\).

Another canonical example is the function \(f_n(x) = n * 1_{(0, \frac{1}{n}]}\). This function converges to the zero function so \(\mu(\lim f_n) = 0\), but \(\mu(f_n) = 1 \forall n \implies \lim \mu(f_n) = 1\). This is another case of us unable to bound $f_n(x)$ by any dominating function.