When you see the C++ standard’s specification on value categories, it’s likely your eyes gloss over and you think to yourself - “why do I ever need to know this?”. At least that’s what I thought when I first took a glance. Over the years, I’ve ran into issues assuming a simplistic model of value categories, and I regret not taking a long hard look at the standard in the beginning. This is my attempt to explain value categories in a fun history lesson (at the time of writing, this view is representative of up to C++20).

Table of Contents

CPL (early 1960s)

According to the standards, the archaic language CPL used the terms “right-hand mode” and “left-hand mode” to describe the semantics of particular expressions. When an expression was evaluated in left-hand mode, it yielded an address, and when it was evaluated in right-hand mode, it yielded a “rule for the computation of a value”. In C/C++, the rule is executed and we retrieve a value on the right hand side.

C (1970s)

Now come C, which started using the term “lvalue” in its standards. People debated on whether the “l” in “lvalue” stood for “locator” or for “left-hand”, but one thing was for sure - it refers to an object. This term, in C, is used to describe an entity that is in storage somewhere, with a location. You can access an object with the name of the variable, or pointer dereferencing its location. Here are some examples of lvalues in C:

int a; // a is an lvalue

int* b; // *b is an lvalue

int c[10]; // c[0] is an lvalue

struct e { int x; }; // e.x is an lvalue

C++98 (1998)

Extensions to lvalues

When C++98 came out, it adopted the idea of an “lvalue”, and used the term “rvalue” for any expression in C++ that was not an lvalue. It also added functions into lvalue category:

void f() {} // f is an lvalue

Introduction to rvalues

rvalues are basically what C considered non-lvalues. However, there are a few caveats with the concept, like the lvalue-to-rvalue conversion:

3; // 3 is an rvalue

'a'; // 'a' is an rvalue

int a, b; a = b; // the expression `b` is converted to an rvalue in `a = b`.

Don’t believe me? Here’s the clang AST dump which clearly says that b is implicitly casted to an rvalue:

...

`-DeclStmt 0x559e56a03270 <line:3:5, col:14>

`-VarDecl 0x559e56a031b8 <col:5, col:13> col:9 a 'int' cinit

`-ImplicitCastExpr 0x559e56a03258 <col:13> 'int' <LValueToRValue>

`-DeclRefExpr 0x559e56a03220 <col:13> 'int' lvalue Var 0x559e56a030f8 'b' 'int'

The intuition here is that a wants to be given a value, so we retrieve the value that b has and load it into a CPU register to then give to a (in reality it could be done differently). The state of the value being in a register is considered an rvalue, and hence we cast the expression b into an rvalue.

References are added

In addition, C++ introduced a nice abstraction called references(which we now know as lvalue references). If you’ve written C++, you’ve likely used it. Here’s an example of a reference:

int a;

int& b = a;

int& c = 1; // invalid! 1 is not an lvalue.

Bjarne Stroustup explains that the reason he added references in C++98 was a need for syntactical sugar for operator overloading. However, Ben Saks explains in his CppCon talk that some operating overloading functions are simply impossible to perform given the C++ standard:

struct integer {

integer(int v) : value(v) {}

int value;

};

// This doesn't actually modify i

void operator++(integer i) {

i.value++;

}

// This is ill-formed and won't compile -

// There is already an operator++ for integer*

// which moves the pointer itself.

void operator++(integer* i) {

*i.value++;

}

// This is our only option.

void operator++(integer& i) {

i.value++;

}

const references - replacing pass-by-value

With the introduction of references, C++ programmers now have the option to pass by reference into a function rather than pass by pointer in C. However, this came with its own set of challenges. Suppose we allow addition of two integers:

// bad! We copied the integer when it wasn't necessary.

integer operator+(integer i1, integer i2) {

return integer(i1.value + i2.value);

}

// ill-formed and won't compile.

integer operator+(integer* i1, integer* i2) {

return integer(i1->value + i2->value);

}

So the C-style operator overloading won’t work here as expected. Let’s try references!

// bad! doesn't work for all situations!

// It works for:

// integer i1(2);

// integer i2(3);

// i1 + i2;

// integer(2) + integer(3) should yield integer(5)

// but these are rvalues, so it won't compile!

integer operator+(integer& i1, integer& i2) {

return integer(i1.value + i2.value);

}

// This is our only option.

integer operator+(const integer& i1, const integer& i2) {

return integer(i1.value + i2.value);

}

The reason that only const integer& works like this is because of temporary materialization which binds the temporary integer(2) and integer(3) to i1 and i2 respectively, and they will exist in memory somewhere.

This is so confusing, why did they have to make const and non-const references behave differently for rvalues?

Consider the case:

void increment(integer& x) {

++x;

}

int i = 0;

increment(i); // error! No matching function.

Here, the developer is probably thinking - “I’ll pass in an int because it’ll get implicitly converted to an integer, and it’ll get incremented”. If this was allowed, then it would look something like:

- The expression

iinincrement(i)is casted to an rvalue via lvalue-to-rvalue conversion. - The value of

iis implicitly converted tointegerby constructor conversion. - A temporary

integeris created, which doesn’t necessarily have to have storage (we already fail here!) - In the function, the temporary

integeris incremented, NOTi.

Along with other reasons, the C++ committee thus thought there was no reason for non-const references to bind to temporaries. Allowing this for const is totally fine though, because we aren’t expecting the arguments to change after the function call.

The fact that sometimes rvalues could “materialize” and exist in storage in the limited scope of the function, and sometimes not have storage at all must be confusing. This is why C++ further split up the concept of rvalues and defined the materialized values as xvalues, for “expiring values” and no-storage values as prvalues, for “pure rvalues”.

Let’s run through an example:

integer x(3); // `x` is an lvalue

x = 4; // `4` is an rvalue, and implicitly converted to `integer(4)`, also rvalue.

x + x; // `x`'s are lvalues, and converted to rvalues (prvalues)

integer(2) + integer(3); // `integer(2)` is a prvalue, and it is materialized as an xvalue

Life went on for C++ developers who came to live with these set of rules with lvalue and rvalue` (which is further broken up into xvalues and prvalues). However, C++11 came and value categories became more complicated.

C++11 (2011)

One of the biggest optimizations to the C++ language paradigm occurred in C++11, in the form of move semantics. Prior to C++11, there was no standardized way to “rip out” contents from one object to be used in another. This is especially important for heavyweight data structures which may allocate large buffers transparently to hold objects, such as std::vector<T>. We can declare an object of type T “move-able” if it’s an rvalue reference, denoted as T&&. We can also turn lvalues into rvalue references by using std::move. Let’s run through a simple example:

#include <vector>

#include <thread>

#include <chrono>

#include <iostream>

template <typename T>

class data_structure {

public:

data_structure() = default;

data_structure(const data_structure<T>& clref) {

// Usually in here we would use `new` and `memcpy` or `std::copy(...)`

// to copy contents large buffers from clref to this object.

// We simulate that with a long sleep.

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::seconds(1));

}

data_structure(data_structure<T>&& rref) {

// Usually in here we would rip out the contents from rref and leave rref in

// a valid but unspecified state.

// This is as simple as a pointer assignment.

// It's on the order of nanoseconds.

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::nanoseconds(1));

}

};

int main() {

data_structure<int> d;

// Copying

std::cout << "Copying is slow..." << std::endl;

data_structure<int> cd(d);

// Moving

std::cout << "Moving is fast!" << std::endl;

data_structure<int> md(std::move(d));

}

As you can see, std::move(d) essentially casts the current data_structure<T>& to data_structure<T>&&, and we trigger the move constructor. I talk about these rvalue references further in this blogpost.

So what does the above have anything to do with value categories? Recall that before C++11, we have the notions of lvalues and rvalues which are further divided into xvalues and prvalues. The reason rvalues were split into the two was because it could be temporarily materialized into an expiring value using const references. Similarly, with std::move, we can also consider the moved lvalues as expiring values(xvalues) as well. This is because when we allow the lvalue reference’s contents to be moved, it usually should be considered expired as it’s left in a valid but unspecified state.

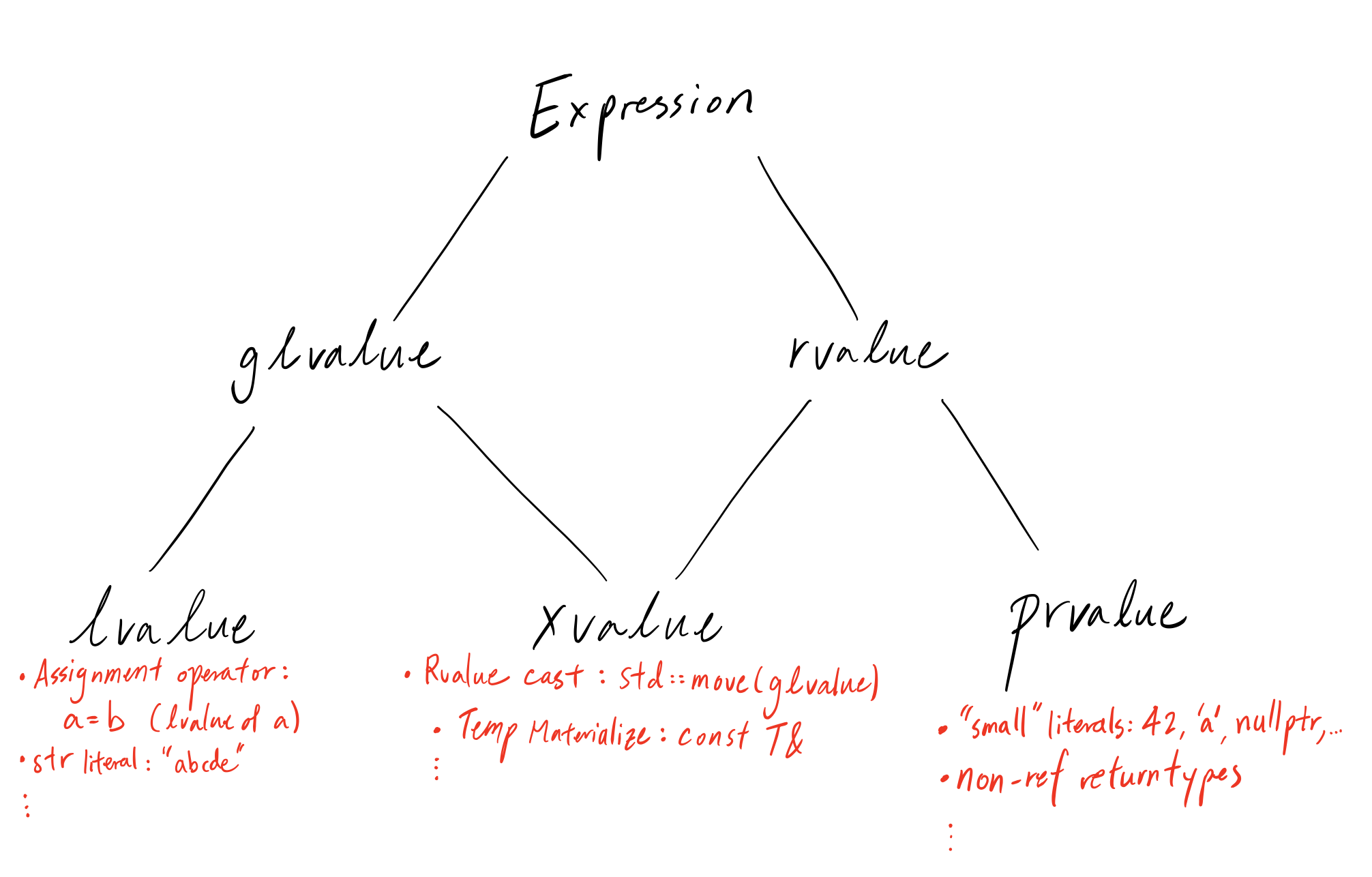

Now this is where things become a little confusing. Bear with me here. We have rvalue divided into xvalue and prvalue, then we should ideally divide lvalue into xvalue and plvalue(for “pure” lvalues) right? No. The standard commitee decided to call what we coined plvalue as lvalue, and we coined lvalue as glvalue, or “generalized lvalue” which encompasses xvalue and lvalue. The tree looks like the following:

So why didn’t the standard committee use the term plvalue?

To be fair, prvalue is “pure” in the sense that it does not have storage semantics(even though it may be stored in memory somewhere if it doesn’t fit in registers), meanwhile xvalues have temporary storage. The concept of plvalue doesn’t really make sense since both itself and xvalues would have storage semantics. In this sense, lvalue is a bucketing term for objects that don’t expire. Generalized lvalues covers all objects, expire or not.

This is basically an accurate picture of the current state of value semantics in C++. It’s only confusing because of the names and historical context. If we see the evolution of these terms, it makes the bigger picture a bit easier to understand. To recap, any expression can either be glvalue or rvalue. glvalues can be either lvalues(non-expiring objects) or xvalues(expiring objects). rvalues can be either prvalues(no storage semantics) or xvalues(prvalues that temporarily materializes into objects).

C++17 (2017)

The definition of what is a prvalue and what isn’t has been changing frequently, but one of the most important and non-obvious things we should mention is the copy ellision rules involving returning prvalues. In C++17, copy ellision is now guaranteed for function calls returning prvalues, as in they never undergo temporary materialization. This is in a class of optimizations called RVO (return value optimization), and it has important implications.

More on RVO

It’s important to note what kinds of RVO there are. There is the type of RVO that works on lvalues, which is also called NRVO, for “named return value optimization”. There is also another RVO that works on prvalues. Usually, RVO on prvalues is often more powerful than NRVO. In the standard there is no RVO for xvalues.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class obj {

public:

obj() {

std::cout << "default ctor" << std::endl;

}

obj(const obj& o) {

std::cout << "copy ctor" << std::endl;

}

obj(obj&& o) {

std::cout << "move ctor" << std::endl;

}

};

obj make() {

return obj();

}

int main() {

obj o = make();

}

Previously, the standard didn’t specify which one would be guaranteed to be faster than the other:

(1)

Foo make_foo() {

Foo f;

// Move semantics

return std::move(f);

}

(2)

Foo make_foo() {

// RVO

return Foo();

}

Before, compiler writers could technically invoke the move in case (2), resulting in identical performance as (1). Now, they must enforce zero-copy pass-by-value semantics on (2) since Foo() is a prvalue. In clang and gcc that support C++14 and below, passing in -fno-elide-constructors allows for (2) to not be optimized and manually create the object and then perform a move(if move semantics are valid for Foo). In C++17, the compilers ignores the flag and continues to elide it anyways because Foo() is a prvalue and it must be copy elided. I suggest this blogpost if you’re interested in the subject.

Conclusion

From loosely used terms in CPL to an almost lawyer-level specification, value categories has come a long way. With a clean and clear set of rules on value categories, it is easier for the standard commitee to add optimizations to the language, like move semantics and improvements on return value optimization. This is also one of the few things in the C++ standard that is ubiquitously used in other concepts, so with a basic fundamental knowledge on these value categories you’ll an easier time navigating cppreference.com. Hope you enjoyed!